another front yard

We are so far west into Virginia that we are only about 10 miles from the state line with Kentucky. Evidence of all of this rural, mountain quietude is the absence of radio or TV reception. Even our satellite dish will not pick up a signal in this deep valley. There is one scratchy AM radio station (from Kentucky) if we ever git a hankerin' for some blue grass. Fortunately for us, we do have access to the Internet so we are still able to hear the weather report and follow the Broncos!

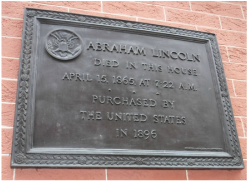

John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, took ad-vantage of the opportunity to enter the Box and shoot Lincoln. The play did not finish its third Act that evening.

Just the right people were in the audience that night. The chief of police. Two doctors. Some of Lincoln's staff, Generals, his secretary, and aides were there, too. First aid was immediate. They moved President Lincoln across the street to the Petersen House -- Lincoln was too fragile to transport to the hospital. Vice President Andrew Johnson was notified. The Chief of Police immediately set a $100,000 reward for the capture of Booth.

His funeral train traveled 1700 miles on its way back to Illinois. There were many open casket viewings at the stops along the rail line. People were so distraught, and wanted to see Lincoln one last time, that they were sleeping along the streets and railroad tracks in order to get a glimpse. It was a terribly sad time for our country.

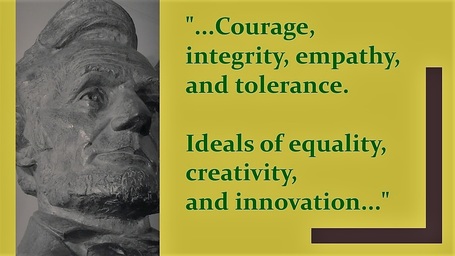

One of the displays in the Visitors' Center opines how a humble woodcutter could become such an endearing role model for so many Americans. The display suggests that it was because during his life -- and throughout America's worst crisis -- Lincoln championed effective principles of leadership. The thoughtful script on the display concludes with these words:

baltimore:

home of the crab cake

Today, the stretch of harbor from Inner Harbor to Fells Point offers a trendy lifestyle for this century's up-and-coming millenial crowd. The area appears to have an electric nightlife. The blend of the olde with the new is conspicuous, however. High-profile "contemporary colonial" condos and parking garages stand where busy warehouses were once the hub of vibrant, local merchantry. Gift shops, taverns and restaurants have replaced cobbler shops, fisheries, and coopers. An abandoned rail line weaves a broken turn but serves only as a reminder of past trolly routes. The historic wharfs now greet a different kind of visitor while assuring this waterfront's nation-forming past is not forgotten.

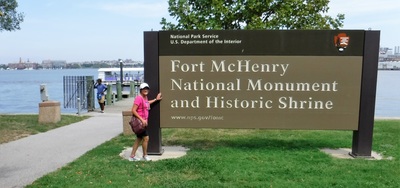

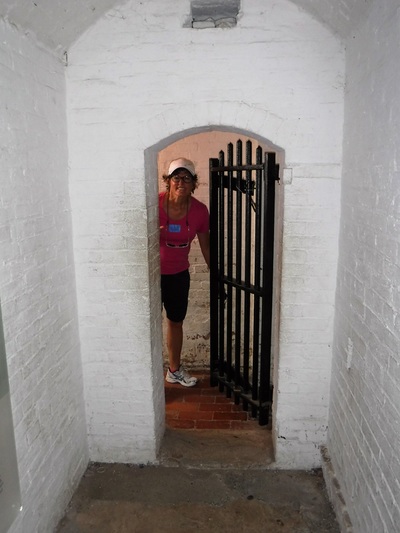

Across the harbor, Fort McHenry invincibly stands guard over Baltimore as it has for three wars. It was 'Defenders Day' (actually a full week-long event) while we were visiting; a water taxi was needed for easy access to the National Park. The fort is fully restored and great fun to explore. There still flies proudly a 15-star flag over the ramparts. Many thanks to the team of informative NPS Rangers and costumed interpreters that made our visit very memorable. Back on the harbor-side, a stop into one of the celebrated Thames Street shoppes for some homemade crab cakes could not be overlooked -- they were the best we've ever had, and a great way to wrap up our visit to the area!

cannoneer rodgers

at gettysburg

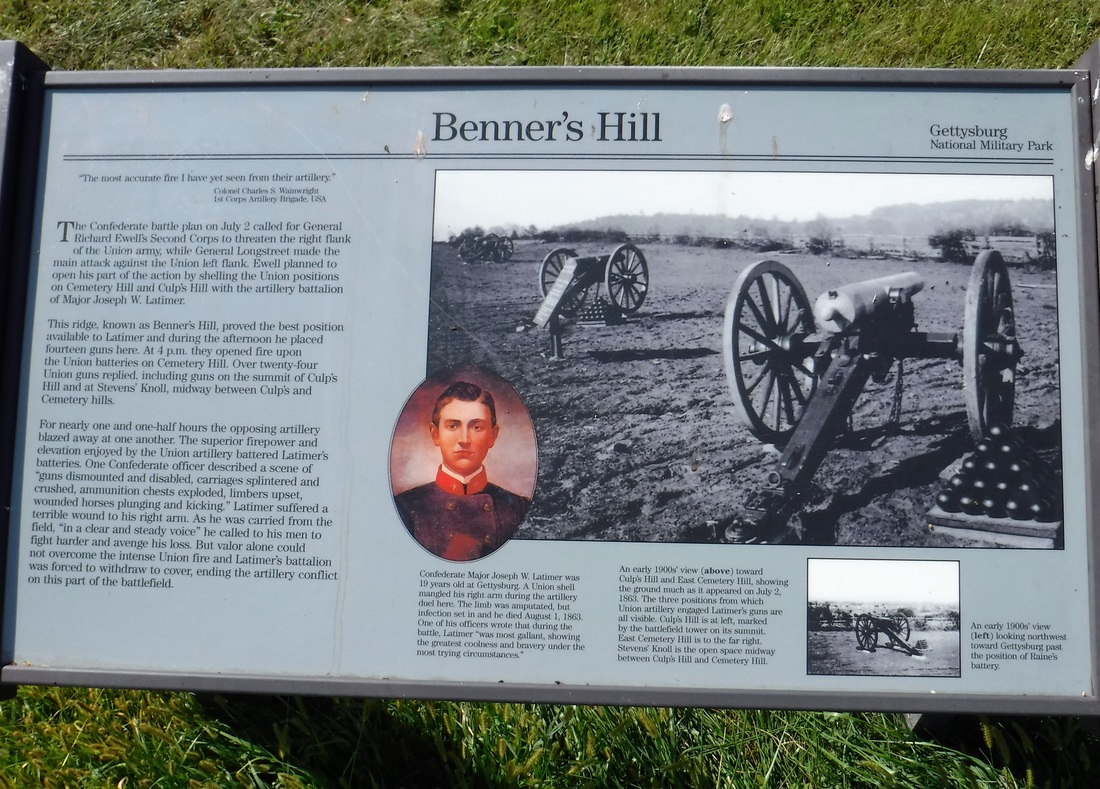

| Ken’s great-great-grandfather, Charles Robert Rodgers, was born near Front Royal, Virginia, in the 69th District of Warren County, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley on 18 August 1845. Charles led an adventurous life which included time served under General Stonewall Jackson in the Civil War, as well as a devotion to the hobbies of photography and steam railroading. Charles was well-liked, a willing servant, and always eager to be helpful. Charles became one of his community’s best-known citizens. At Newtown, Virginia, on 10 March 1862, Charles enlisted in Captain Cutshaw’s battery of light artillery, a Confederate army unit composed of men from the Newtown-Middletown area and part of the famous “Stonewall” Brigade. In September of that year Cutshaw’s battery was merged into Captain John C. Carpenter’s battery, and re-named the Alleghany Artillery. Though counts vary, the Alleghany Artillery was at one time as large as 97 men. Charles remained with the Alleghany Artillery for the duration of the Civil War as a member of the Army of Northern Virginia. During the war, Charles was a cannoneer in some twenty-one separate engagements, including the Battles of Winchester, Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Wilderness, and Spotsylvania. On 2 July 1863 in the second day of fighting at Gettysburg (reporting under Ewell's Corps, Johnson's Division, and Latimer's Battalion), The Alleghany Artillery of the Army of Northern Virginia played a most prominent role in the great cannonade against the Union artillery that was positioned on both Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill. One of four artillery units in Latimer’s Battalion, the Alleghany Artillery was set mid-rank in a line of 16 guns atop Benner’s Hill, about one-quarter mile away and to the northeast. In final position, the most dynamic artillery volley of the Civil War began at 4:00 that afternoon. It continued for over two hours. With 24 guns of the Union artillery returning fire from higher ground, the 16 Confederate cannon were no match. To add insult to injury, Ewell's simultaneous infantry attack of Cemetery Hill was also unsuccessful. The battle at Gettysburg was the bloodiest of the Civil War. Some of the Union guns on the left managed to enfilade the Confederate position which caused Charles' battery to suffer severely. Having exhausted 439 rounds in two Napoleons and two 3-inch guns, and without any remaining ammunition, the Alleghany Artillery was forced to withdraw with the Battalion. Casualties were 5 men killed, 24 wounded, and 9 horses dead. Charles was among the wounded. The other three C.S.A. artillery units also suffered greatly. | On 19 September 1864, during the Third Battle of Winchester, Charles was wounded again, and captured by Federal forces, only ten miles from his home. He had just turned 19 in August. After being released from the Federal Prison Camp at Point Lookout, Maryland, at the war’s end, Charles could only find work in agriculture. He soon became disenchanted with such backbreaking work and became interested in photography—a new technology that was becoming popular. In 1870 he opened a photographic studio in Winchester, Virginia. He was no doubt employed in this profession at the time of his marriage to Mollie Cole. Unfortunately, after a short time, the business failed, but since both he and his father had previously done railroad work, he was able to get employment with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as a Conductor on the route between Martinsburg, West Virginia, and Cumberland, Maryland. Around 1874, Charles and Mollie moved to Grafton, in Taylor County, West Virginia, a busy railroad town on the main line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, where the couple lived out their remaining years. During his lifetime, Charles was most proud of his association with the “Stonewall” Brigade. It is not known whether or not he attended the great reunion of “Stonewall” Brigade veterans held in Lexington, Virginia, in 1890, but he did return to visit the Valley on occasion, to visit friends, relatives, and some of the old campaign sites from the war. Charles died on 6 November 1902 as the result of a fall at the Grafton Hotel, which still stands today. He was assisting some friends from church to hoist a rope holding a banner and by accident was thrown off his feet and down the concrete steps leading up to the hotel’s main entrance. The fall was fatal; he was only 57. He was buried in Bluemont Cemetery in Grafton. Charles was a good man with a generous heart. He enjoyed many of the same passions that I do. It is for these reasons that Deb and I named our first born son after Charles Robert Rodgers. |

breaking news:

skirmish at

hanover junc'n STATION

| We were almost to Hanover Junction. About ten miles north of New Freedom we began to hear quite a commotion in the Pullman Car in front of us. The confederate soldiers had jumped our train! Fortunately, there was a small encampment of Union soldiers just around the next bend; the engineer pulled back hard to get the train stopped in time. While we got the Rebel off of the train, he caught by surprise the Union soldiers there who were enjoying their Sunday afternoon. | |

confederates

at glenrock station?

There was a lot of whooping and hollerin' from the other passengers as the soldiers lumbered off the train in their tattered grays. In the video, if you look closely, you can see one of the Rebels on the path in front of the train, and then cross the tracks after the train passes. I wonder what they were up to? Hmmm ... You don't suppose they have been laying in a ravine for the last 153 years waiting for orders to come from south of the Mason-Dixon Line, do you? Maybe I should alert the TSA?

| Ken wanted to pin down the exact location of Mr Lincoln's most famous address. Abe remained stonefaced. |

another front yard

(and cool railroad stories)

| [Ken 08/29/2016] We are in the peaceful borough of New Freedom, Pennsylvania, at Summit Grove Christian Conference Center. Summit Grove got its start as a Methodist Revival Encampment when the Northern Central Railroad appeared here in the 19th century. Though the camp and the town have been nicely updated since those days, they still reflect much of their classic and cultural pre-Civil War legacy. |

| Less than a mile north of the Maryland border, we are only a few hundred yards from the small downtown of New Freedom, and about halfway between Lancaster (think "Amish") and the Gettysburg region. About 35 miles to the south is Baltimore. This burough is split by a historic rail line that runs north to south through the center of town An inviting bike/running path has replaced two pairs of rails. When the "York" steam engine pulls into town it is breathtking! | |

Perhaps the railroad is most famous as the presidential route of Abraham Lincoln when he made his way from Washington DC to deliver the Gettysburg Address. It is rumored that he may have written his final draft of the Address while on that train. In April 1865, President Lincoln passed through New Freedom one final time as his funeral train made a stop at the station here. It is humbling to consider the depth of history in these rails.

Footsteps from downtown, arresting, gentle hills of fertile farmland offer a refreshing experience from the gridlocked and crowded upper New England areas that we toured last month! The combination of American flags with pumpkins on porches takes me back to another time. We went to a fair in the New Freedom community park and it seemed we were comfortably back in the the 1950's; it was so classically folksy!